Further direction from courts and legislature may be necessary: Fasken's Peter Downard

The Ontario Superior Court recently dismissed the anti-SLAPP motion brought by Canadaland and journalist Jesse Brown in response to the defamation suit arising from their podcast examining the WE Charity. The court will now proceed to hear the merits of the defamation claim.

The plaintiff, Theresa Kielburger – the mother of WE Charity’s founders – also brought a defamation claim against a guest on the podcast, journalist Isabel Vincent. But the court granted Vincent’s anti-SLAPP motion and dismissed the claim against her.

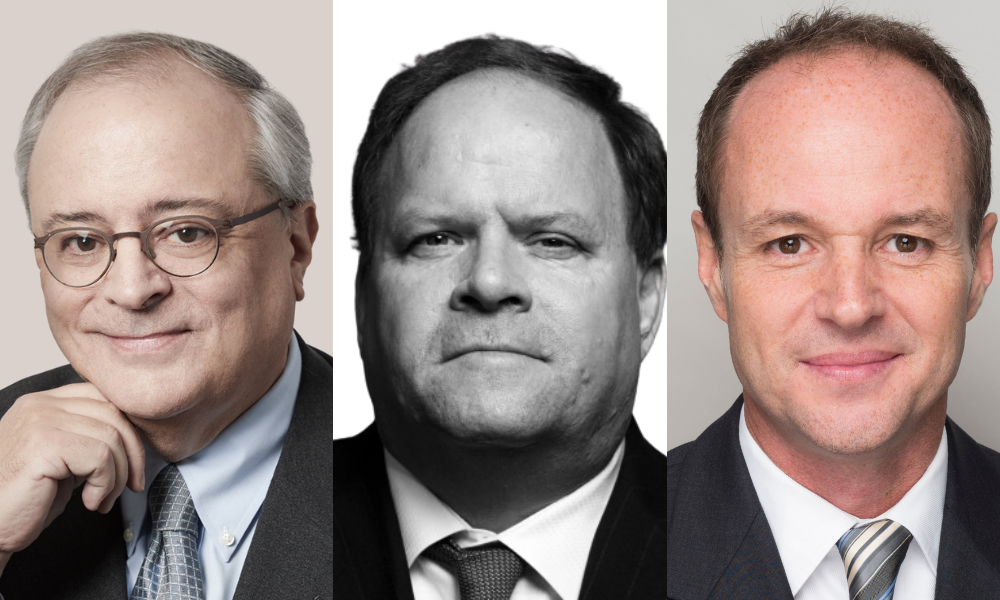

Peter Downard is a partner at Fasken and counsel for the plaintiff. He is the author of “The Law of Libel in Canada” and was one of three appointed members of the Attorney General of Ontario’s advisory panel on strategic litigation against public participation (SLAPP), which led to Ontario’s anti-SLAPP law.

Downard says Kielburger v. Canadaland Inc., 2024 ONSC 2622 is an example of how the anti-SLAPP legislation is being misused. These are meant to be “concise, preliminary screening motions,” he says, and this case – like numerous others – was “far too factually and legally complicated to properly be the subject of an anti-SLAPP motion…

“This case took just as much work as a trial, and I’ve seen many other anti-SLAPP motions – including that I’ve been involved in – of which one could say the same thing.

“My concern, for larger systemic purposes, is that lawyers have to approach these motions in the spirit in which they are intended,” says Downard. “They may need further direction from judges and from the legislature in that respect.”

For example, the legislation contains a rule where a party who brings an anti-SLAPP motion will not be required to pay the plaintiff’s costs if unsuccessful. “Too many lawyers have taken that as permission to take a free throw,” says Downard. This results in complicated motions, extensive records, and cross-examinations, which impose a significant burden on the plaintiff, while the defendant “may not be very much worse off for having used the process in a way that, in my opinion, is inconsistent with the spirit of the legislation,” he says.

The defamation claim stemmed from Canadaland’s 2021 podcast series on the WE Organization, “The White Saviors.” The podcast revisited a passage from a 1996 Saturday Night article written by Vincent that said donations made to the WE Organization – then called Free the Children – were being deposited directly into the Kielburger family’s bank account. The organization was not yet a registered charity, and Kielburger said Vincent’s passage insinuated she was misusing or misappropriating the funds.

In the anti-SLAPP test under s. 137.1 of the Courts of Justice Act, the person facing the defamation claim brings a motion asking the judge to dismiss the proceeding if they can satisfy the judge that the proceeding has arisen from an expression related to a matter of public interest. The judge will not dismiss the action if the other party satisfies them of two things. One is that there are grounds to believe that “the proceeding has substantial merit” and “the moving party has no valid defence.” And two, the harm from the allegedly defamatory expression is serious enough that the public interest in continuing the proceeding outweighs the public interest in protecting the expression.

Iain MacKinnon, a lawyer at Linden & Associates, acted for Vincent. He says the most significant aspect of the decision was the court’s finding that general damages are presumed in a defamation action. This is relevant to the third part of the test, where the court weighs the harm of the defamation against the public interest in protecting the expression.

“There's been, I would say, almost conflicting decisions about how far a plaintiff has to go to establish harm or damages in a defamation action,” he says.

On the first stage of the s. 137.1 analysis, the parties agreed that the expression related to a matter of public interest. The court found that there was substantial merit to the defamation for the podcast’s re-airing of the “money passage” from the Saturday Night article.

As to whether Canadaland and Vincent had a valid defence, the defendants raised three potential defences: privilege, responsible communication and reportage, and fair comment.

The defendants argued that the statements consisted of a “fair and accurate report” of judicial proceedings before an open court, which the Supreme Court of Canada has deemed privileged. However, the plaintiffs responded that the defamation was an altered restatement of a passage from a magazine article that was the subject of a settled legal dispute that never made it to court. The restatement “is not cloaked in the privilege it might have received had it come directly from a court hearing,” they said. Similarly, other statements in the podcast on the matter went beyond what was subject to the lawsuit. Ultimately, the court found that this case presented no valid privilege defence.

For a defence of responsible communication, the defendant must demonstrate that the publication was on a matter of public interest and was published responsibly and diligently concerning the underlying facts. The plaintiffs argued that the defendants fell short of this requirement by failing to contact Theresa Kielburger for comment. The court did not accept the defendants’ rationale that Theresa was not a party to the earlier lawsuit, and they were therefore not required to contact her and concluded that there was no reason to believe the defence of responsible communication would be applicable.

William McDowell is a partner at Lenczner Slaght and was also counsel to Kielburger. He notes that, in addition to contacting subjects of media reporting, responsible communication also requires the journalist to adequately investigate the claims related to them.

“A lot of media lawyers kind of skim over that,” says McDowell. “It's not enough just to put the allegation to the target. You have to actually do your best to figure out whether the allegation is true or not before you move on.”

For the fair comment defence, the allegedly defamatory statement must be on a matter of public interest, based on fact, and recognizable as comment. The comment must pass the test: could anyone “honestly express the opinion on the proved fact.” Even where the defendant passes the test, the plaintiff can defeat the defence by showing the defendant was malicious.

The claim that the plaintiff deposited thousands of dollars in donations into the family’s personal bank account did not qualify as fair comment, which the SCC has described as “a mere matter of opinion, and so incapable of definite proof.” According to the court, this statement was one of fact, not opinion, and the evidence “goes a long way toward establishing” that it was untrue.

On the other hand, the court said Vincent’s statement about why the settlement came about is more opinion than fact.

While Canadaland failed to demonstrate that they had a valid defence of fair comment, Vincent succeeded in doing so.

In weighing the harm of Canadaland’s defamation against the public interest in protecting its expression, the court noted Theresa Kielburger’s passionate testimony describing the emotional impact of the claim made in the podcast. The court concluded that the alleged defamation was more a “personal attack on the plaintiff’s character” than “any genuine discourse on the WE Organization and its role in Canadian politics.” The court found the harm outweighed the public interest in protecting the expression and dismissed the anti-SLAPP motion. The defamation action will proceed.

The court granted Vincent’s motion and dismissed the defamation action against her.