Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada is at the top of the list of federal departmental spending on legal fees as newly released public accounts figures show the government is pouring big money into litigation over First Nations issues.

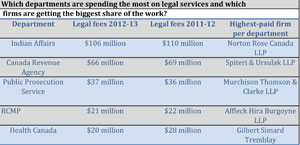

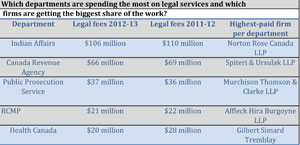

In a year that saw aboriginal concerns take centre stage with the Idle No More movement and Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence’s hunger strike, public accounts figures for 2012-13 released at the end of October show Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada with a legal tab of $106 million. That amount far exceeds the legal tab at the Canada Revenue Agency, the department that was next on the spending list. The CRA spent $66 million.

With the federal government aggressively pursuing economic development on lands subject to claims by First Nations and movements like Idle No More providing aboriginal groups with “political capital,” the legal process is becoming even more complex and difficult to get through, according to David McRobert, a member of the Ontario Bar Association’s aboriginal law section.

The fact that aboriginal communities are gaining political capital also means the federal government is under growing pressure to spend more money to move things along, says McRobert.

The Aboriginal Affairs Department’s spending was also at the top of the list last year, when it racked up $110 million in legal services.

When it comes to significant unresolved legal issues, land claims also top the list in this year’s public account documents. Comprehensive land and specific claims make up a significant portion of the “large and significant” matters pending against the government.

“Comprehensive land claims arise in areas of the country where aboriginal rights and title have not been resolved by treaty or by other legal means,” the public accounts report states.

“There are currently 81 comprehensive land claims under negotiation, accepted for negotiation or under review.”

According to government estimates, “to a point where quantification is possible,” it has a liability of about $4 billion in comprehensive land claims.

According to McRobert, there have been resolutions to about 24 comprehensive claims so far in Canada.

The process is “incredibly time consuming,” says McRobert. “Usually, you’re talking about a lot of money.”

Since the early 1980s, there have been more than 175 cases brought before the courts involving corporations that want to pursue development on aboriginal lands, says McRobert. In 90 per cent of cases, “the aboriginal people win,” he adds.

In a recent landmark ruling, the federal government lost a 13-year legal battle over Métis status. The case was “a travesty,” says McRobert, adding there’s “absolutely” a better way to resolve these issues.

“The direction from the Supreme Court of Canada has been fairly clear — resolve these things, resolve these things with the aboriginal people. . . . You have to work with First Nations.”

The drawn-out process is also “a tragedy for [First Nations] communities,” says McRobert. Even when the parties reach a deal and the communities have to pay 10 per cent of their settlement to lawyers, “that’s money not spent on education,” he adds.

Instead of lengthy legal battles, the parties should be engaging in “serious” roundtable talks, according to McRobert.

In the public accounts, the government noted it would “pursue a settlement agreement with the First Nation when a claim demonstrates an outstanding lawful obligation.”

The document also says there are “thousands of claims and pending and threatened litigation cases outstanding against the government.”

“These claims include items with pleading amounts and items where an amount is not specified. While the total amount claimed in these actions is significant, their outcomes are not determinable.”

In terms of specific claims, which deal with “the past grievances of First Nations related to Canada’s obligations under historic treaties or the way it managed First Nations’ funds or other assets,” there are currently 448 of them under negotiation, an increase from 439 in 2012.

The government estimates a liability of $3.8 billion for specific claims “that have progressed to a point where quantification is possible,” according to the government.

For its part, Aboriginal Affairs maintains it’s doing a good job of spending taxpayers’ money. “Our government treats taxpayers’ money with the utmost respect and we require that government business be done at the lowest possible cost to taxpayers,” said spokeswoman Erica Meekes.

In a year that saw aboriginal concerns take centre stage with the Idle No More movement and Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence’s hunger strike, public accounts figures for 2012-13 released at the end of October show Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada with a legal tab of $106 million. That amount far exceeds the legal tab at the Canada Revenue Agency, the department that was next on the spending list. The CRA spent $66 million.

In a year that saw aboriginal concerns take centre stage with the Idle No More movement and Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence’s hunger strike, public accounts figures for 2012-13 released at the end of October show Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada with a legal tab of $106 million. That amount far exceeds the legal tab at the Canada Revenue Agency, the department that was next on the spending list. The CRA spent $66 million.